In 1942, more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans were abruptly removed from their homes and forced to re-locate on ten internment camps scattered through-out the western United States. Among the interned was Kenichi Zenimura; a star player, coach and organizer in the California Japanese League. Upon arriving at the Gila River War Relocation Center, he immediately began transforming a patch of harsh Arizona desert into a beautiful baseball oasis. Considering the lack of resources available to him, this required a rare brand of ingenuity. According to the Nisei Baseball Research Project, he extended a pipe from one of the laundry rooms to grow the outfield grass. Children were recruited to meticulously remove the pebbles from the infield dirt and re-purpose them as ground cover in the dugouts and stands. Along with excess wood from the lumber yard, every other post was removed from the perimeter fence and used to construct a backstop and bleachers. Flour was acquired from the dining hall to chalk the foul lines and high-growing shrubs were planted along the path of the outfield "wall". Other internment camps built baseball fields of their own, but "Zenimura Stadium" was the crown jewel (a literal diamond in the rough).

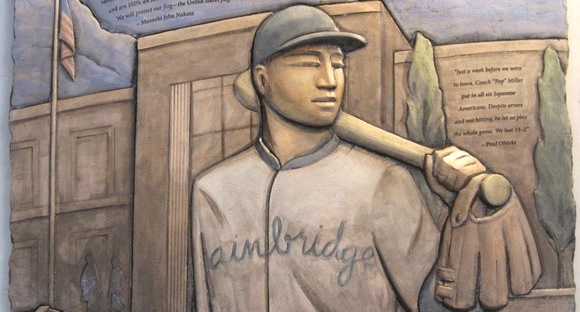

After moving to Fresno as a young man in 1920, Zenimura established himself as a true baseball pioneer. He collaborated with Japanese universities, American semi-pro clubs, and Negro Leagues teams to organize games, tournaments, and three goodwill tours to East Asia. In 1927, when Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig came barnstorming, Zenimura was selected to be a member of the opposing team (as the story goes, he infuriated Ruth with his speed and cleverness on the base paths). So when Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order that effectively evicted people of Japanese descent from the west coast states, Zenimura was more than qualified to help preserve baseball culture for the 13,000 involuntary residents who ended up at Gila River. After his field was complete, he quickly organized a 32-team league, arranged by age group and skill level. In doing so, he provided a temporary escape from their harsh reality and perhaps even a sense of dignity and normalcy.

After moving to Fresno as a young man in 1920, Zenimura established himself as a true baseball pioneer. He collaborated with Japanese universities, American semi-pro clubs, and Negro Leagues teams to organize games, tournaments, and three goodwill tours to East Asia. In 1927, when Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig came barnstorming, Zenimura was selected to be a member of the opposing team (as the story goes, he infuriated Ruth with his speed and cleverness on the base paths). So when Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order that effectively evicted people of Japanese descent from the west coast states, Zenimura was more than qualified to help preserve baseball culture for the 13,000 involuntary residents who ended up at Gila River. After his field was complete, he quickly organized a 32-team league, arranged by age group and skill level. In doing so, he provided a temporary escape from their harsh reality and perhaps even a sense of dignity and normalcy.

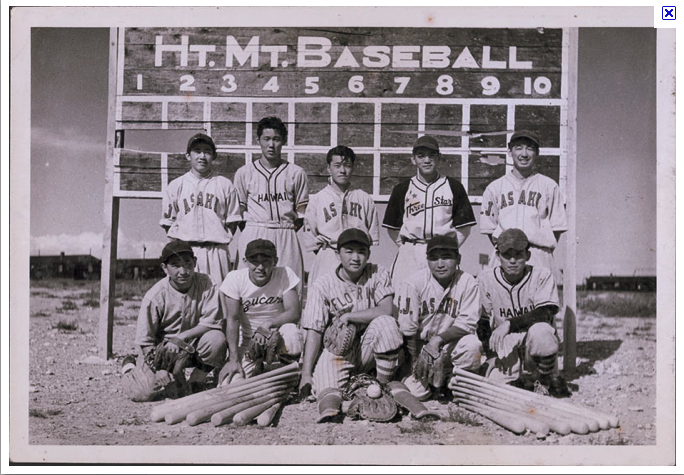

Gila River was one of four facilities that permitted its sports teams to travel. In September of 1944, Zenimura led a club of his best adult players on a 1,200 mile bus trip to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming. Despite some tough competition from their opponents - many of whom had played semi-professional ball before the war - Zenimura's team won nine times in a 13-game series (a 14th game was cancelled due to severe dust storms). For some of the players, it was the first time they had left the Gila River compound in over two years. The players were also sometimes permitted to engage with the external world... taking on teams comprised of camp guards or occasionally entering a local tournament. When the interned Japanese-American teams came to the field, opposing players everywhere knew they were in for some serious competition.

The most famous example of an internment/non-internment match-up occurred on April 18, 1945. Kenichi Zenimura arranged for the Tucson Badgers, a high school team that had just won the Arizona state championships, to come to Zenimura Stadium. They would face the Butte High Eagles, Gila River's strongest high school squad (coached by Zenimura, naturally). The game ended in the 10th inning, when Kenshi Zenimura (Kenichi's son) smacked a two-out single down the third base line to score the winning run. Afterwards, the two teams reportedly shared watermelon and talked about Sumo wrestling. Zenimura later called the game "one of the most thrilling chapters in the history of Gila River baseball". The two coaches arranged a re-match to take place in Tucson, but the school district disapproved, calling the game a "potential security threat".

Gila River, along with most of the other camps, was shut down later that year following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the end of the war. It is one of history's most tragic ironies that the decimation of the internee's cities and families back in Japan, would soon after lead to their freedom at home. This was a horrible price I'm certain most residents would have rather not paid for their release. The Zenimura family returned to Fresno, where Kenichi continued to play competitive ball until the age of 55. He also coached a local Japanese baseball team to two state championships and a national title. In 1979, he became the first Japanese-American inducted into the Fresno Athletic Hall of Fame; eleven years after his death at the age of 68.

Gila River, along with most of the other camps, was shut down later that year following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the end of the war. It is one of history's most tragic ironies that the decimation of the internee's cities and families back in Japan, would soon after lead to their freedom at home. This was a horrible price I'm certain most residents would have rather not paid for their release. The Zenimura family returned to Fresno, where Kenichi continued to play competitive ball until the age of 55. He also coached a local Japanese baseball team to two state championships and a national title. In 1979, he became the first Japanese-American inducted into the Fresno Athletic Hall of Fame; eleven years after his death at the age of 68.

On May 28, 2016, the Friends of Minidoka partnered with the National Park Service to organize a 'Field In a Day' event. Over 160 volunteers gathered on the former site of the Minidoka Relocation Center, in Southern Idaho, to re-build one of the internment camp's baseball fields. The new field symbolizes the impact the sport had on the internees and will be used to teach younger generations about Japanese-American internment during WWII. Photos from the re-build can be seen on the Friends of Minidoka's facebook page.

Sources:

Transpacific Field of Dreams, Sayuri Gethrie-Shimizu, UNC Press, 2012

"Baseball Field at Japanese-American Incarceration Site to be Rebuilt", Kendra Evensen, April 26, 2016

"Baseball in American Concentration Camps", Densho Blog, April 5, 2016

"Matsumoto & Zenimura: U.S. - Japan Baseball Ambassadors", Bill Staples Jr, January 18, 2016

"70th Anniversary: Butte High Edges Tucson Nine in 10th", Bill Staples Jr., April 17, 2015

"Behind Barbed Wire", Philip Byrd, The National Museum of American History, March 18, 2015

"Japanese-Americans Recall Baseball Glory During Internment Camp Years", Tracy Seipel, The Mercury News, October 27, 2014

"When Gila Fought Heart Mountain", Tetsuo Furokawa, February 26, 2010

"How One Japanese-American Runner Took On Babe Ruth", The Christian Science Monitor, May 6, 1997

"Zenimura Field", Nisei Baseball Research Project

"The Dean of Japanese Baseball", Nisei Baseball Research Project

The most famous example of an internment/non-internment match-up occurred on April 18, 1945. Kenichi Zenimura arranged for the Tucson Badgers, a high school team that had just won the Arizona state championships, to come to Zenimura Stadium. They would face the Butte High Eagles, Gila River's strongest high school squad (coached by Zenimura, naturally). The game ended in the 10th inning, when Kenshi Zenimura (Kenichi's son) smacked a two-out single down the third base line to score the winning run. Afterwards, the two teams reportedly shared watermelon and talked about Sumo wrestling. Zenimura later called the game "one of the most thrilling chapters in the history of Gila River baseball". The two coaches arranged a re-match to take place in Tucson, but the school district disapproved, calling the game a "potential security threat".

On May 28, 2016, the Friends of Minidoka partnered with the National Park Service to organize a 'Field In a Day' event. Over 160 volunteers gathered on the former site of the Minidoka Relocation Center, in Southern Idaho, to re-build one of the internment camp's baseball fields. The new field symbolizes the impact the sport had on the internees and will be used to teach younger generations about Japanese-American internment during WWII. Photos from the re-build can be seen on the Friends of Minidoka's facebook page.

Sources:

Transpacific Field of Dreams, Sayuri Gethrie-Shimizu, UNC Press, 2012

"Baseball Field at Japanese-American Incarceration Site to be Rebuilt", Kendra Evensen, April 26, 2016

"Baseball in American Concentration Camps", Densho Blog, April 5, 2016

"Matsumoto & Zenimura: U.S. - Japan Baseball Ambassadors", Bill Staples Jr, January 18, 2016

"70th Anniversary: Butte High Edges Tucson Nine in 10th", Bill Staples Jr., April 17, 2015

"Behind Barbed Wire", Philip Byrd, The National Museum of American History, March 18, 2015

"Japanese-Americans Recall Baseball Glory During Internment Camp Years", Tracy Seipel, The Mercury News, October 27, 2014

"When Gila Fought Heart Mountain", Tetsuo Furokawa, February 26, 2010

"How One Japanese-American Runner Took On Babe Ruth", The Christian Science Monitor, May 6, 1997

"Zenimura Field", Nisei Baseball Research Project

"The Dean of Japanese Baseball", Nisei Baseball Research Project